This month in the continuing “My friend wrote a book!” series… Jessica Clem Barnard’s debut rom-com, April in Paris in June!

(Perhaps a less obvious choice for a negotiation newsletter than last month’s book on perfectionism by Dr. Ellen Hendriksen, or next month’s book on transformative justice by Ora Grodsky. But stay with me.)

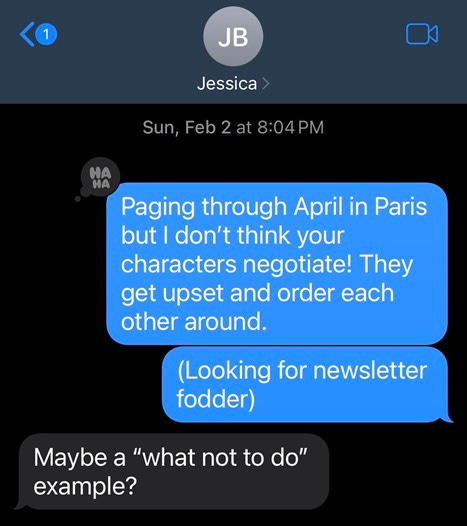

I was looking for a negotiation scene in the book that I could analyze in the newsletter. I didn’t really find one.

Because it’s a romcom, the characters don’t spend a lot of time calmly discussing how to proceed while cultivating mutual understanding. Instead, April and Paul wistfully recall their decades-old Paris tryst while pretending they’re just friends. Sid the cranky neighbor turns out to be a love coach. And Gabriel the startup guy nearly gets himself arrested at the Eiffel Tower, but is rescued by strawberry-wielding Frenchmen.

All that makes for a dynamic story. It would be boring if the characters all sat around saying, “I recognize that we are facing a problem. How can we understand and resolve it together?”

In real life, too, when we reach an emotional crisis point, we lose our ability to negotiate. Our vision narrows, so we can only see what we’re most upset about. We have trouble making conscious, reasoned decisions.

But we can train ourselves to do better.

I am terrible at team sports — mediocre motor control, dislike of sweat, and especially, absolute panic when I get the ball. When you watch pro athletes, they seem to make instantaneous decisions about what to do next. As a spectator, we can see the entire field and observe where everyone is, and it still might take us a minute to figure out the best strategy. The athlete is trained to take in all that information and make a split-second decision. I’ve heard it described as if time slows down — they look around, think about what needs to be done, assess different options, and decide, all in that split second.

After years of practicing negotiation, I feel that same sense of time slowing down while I look around, assess, and make decisions.

One way to cultivate this is to notice that moment of emotional crisis. Observe and name what is happening.

“I think I’m having a meltdown. I feel upset and angry.”

This can be your internal monologue. You don’t have to announce it. Even thinking it puts a little space between you and the strong emotions you are experiencing.

If you can manage that, you have made life-changing progress.

If time has slowed down enough for you to take another step, try imagining alternatives.

Our feelings change over time. If we are very upset, we don’t expect to remain that way forever.

In that space you created between you and your strong emotions, take a moment to imagine that things could be different. What if you did not feel upset and angry? What would that feel like? What would it take?

And finally, ask yourself why — and give an objective answer.

“Why am I feeling upset and angry? Because my partner is being disrespectful.”

This is a start, but “my partner is being disrespectful” is not an objective answer. It’s your interpretation. Your partner might disagree. Someone who didn’t know you, observing your interaction, might see it differently.

So stick to observable facts.

“Why am I feeling upset and angry? Because I feel disrespected. What is making me feel disrespected? My partner’s tone of voice, and the way they keep asking me the same question over and over.”

Now you have something to work with.

This step is extremely difficult to do in the moment. That’s okay. It takes time and practice to separate out your own feelings and judgments from observable facts.

Our friends can help, or therapists, or others who can offer an outside perspective.

This is also where you’ll often hear the advice to make “I-statements” — about how you are feeling, not what the other person is doing. But “I-statements” are blunt instruments. You can say all kinds of things about yourself that aren’t true, and it’s easy to bend an “I-statement” to say something like “I feel angry because of the way I’m being treated [by you].”

Instead, I suggest thinking about how you see the situation, how the other person might see it, and how an outside observer might see it. Come up with a statement that all three of you would agree with.

For instance, you may perceive your partner as being angry, but they would disagree. You can both agree that your partner shut the door and raised their voice. These are observable facts, not interpretations. Facts can help you de-escalate an emotionally intense situation and give you both some common ground to work from.

At the end of step one, you have created some space between you and your emotions. By step two, you are no longer having a meltdown. By step three, you have set yourself up to resolve the problem by finding common ground.

There, I’ve given you a lifetime’s worth of homework.

Thanks for this post, Pia. I've long felt that it's our emotions that hobble us the most when we are negotiating. I wrote and posted a piece yesterday on "reading the room." In it I attempt to give the reader how it feels when everything is going wrong during a negotiation. https://tedleonhardt.substack.com

I am still waiting for the superpower to slow down time when I am having a meltdown, but this is excellent advice (as usual) for what to do when I get there.