Making demands, and resisting them

False binaries like “broccoli or spinach?” aren’t just for toddlers. They work on adults too.

Two stories, same problem.

Candace was prepared to negotiate a salary for her new job – but they sent her an offer letter with a salary number already included, and instructions to sign and return if she accepted the position. Now she didn’t know what to do. “I thought we would have a conversation about salary first,” she said. “Am I stuck? Did I miss the negotiation window?”

A certain person who shall remain nameless but persisted in asking for legal advice, then ignoring the advice and complaining about the consequences, much to the consternation of the advice-giver who eventually stopped giving said advice, asked for legal advice about a form she had been instructed to sign in a continuing dispute. I said, “Don’t sign the form. You have no obligation to sign. There is only downside for you.” But the lawyer on the other side instructed her again to sign it, so she signed.

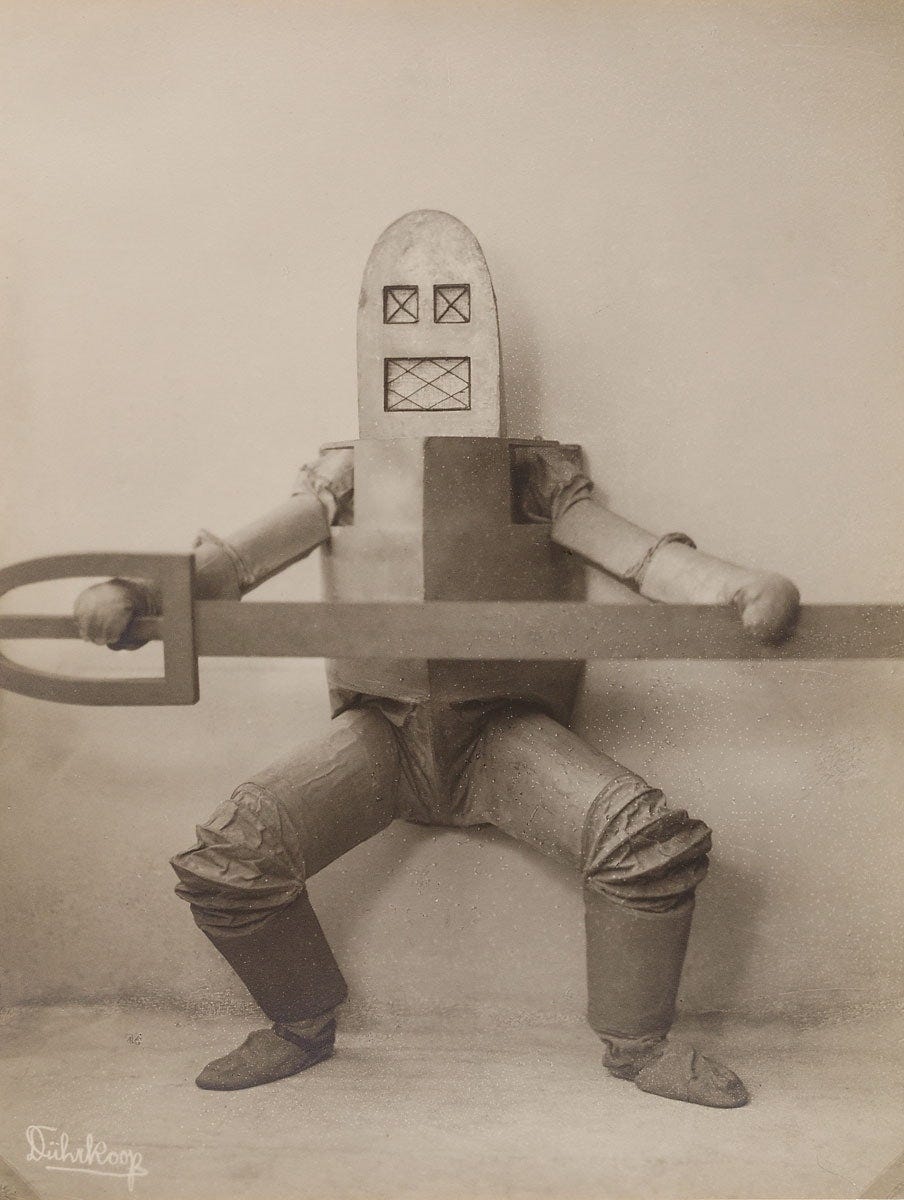

I’ve written before about how toddlers, after a while, get smart enough to figure out that offering two curated options, A or B, is a parental trick. In fact, the toddler is not required to select either option, and can make up their own option C. When you ask, “Do you want broccoli or spinach?” they can yell “NO!” and fling the bowl at you.

By the time we’re adults, perhaps we’ve been bruised by authority a few too many times. When presented with a demand from someone authoritative, we forget we can say no. Or ask a question. Or make a suggestion.

But let’s turn the camera around. Sure, there are lots of ways we could assert ourselves better – but how did we get in this situation in the first place? It’s not because of anything we did wrong. It’s because the other person (let’s call them The Demander) is sending clear and intentional signals that negotiation in this situation is not expected. And The Demander is not explaining why, so we’re left to guess. If we said no, or said anything at all, would it be inappropriate, offensive, humiliating, prohibited? All of the above?

Just like a parent offering their toddler a choice between the red shirt and the blue shirt, The Demander is purposely making you think your options are limited to A or B. Take it or leave it. Or in some cases, presenting only a single option, so you assume it is the only one available. “Sign this and send it back to me.”

When you’re on the receiving end of The Demander

You don’t have to shout, “NO, I’ll never sign your dumb form!” You can ask questions. Surely they want you to understand what you are signing. It would be unreasonable of them to insist on agreement when you haven’t had a chance to fully think through what you are agreeing to.

Candace worried that her negotiation window closed when she received the offer letter. That’s what her Demander wanted her to think. But she hasn’t signed yet, so the window hasn’t closed – and she can open it wider. Even though her Demander has not invited any questions, she can still respond and say, “I was hoping we could have a conversation before finalizing the offer. Would you be available for a phone call within the next few days?”

Nameless Person #2 felt she had to sign the form because a lawyer sent her an official-looking letter. Like Candace, she didn’t see any opportunity for negotiation – there was nothing in the letter that said “Contact me if you have questions,” or “If you choose not to sign, let me know.” It just told her to sign. Again, she had not actually agreed to anything yet, so she could have called and said, “I’d like to talk to you about this. I wasn’t aware I had a legal obligation to sign anything like this. Can you explain?”

Being The Demander

Isn’t it kind of evil to make demands like that? Trick someone into thinking they have no options?

Well, when you say it like that it sounds bad. But you’re not actually taking away their options, or misleading them. You’re guiding them in the direction you want them to go.

Freddie had valuable information to contribute during a presentation at work, but the person in charge was not setting aside any time for her to speak. “How can I convince him that what I have to say has value?” she asked.

“Don’t,” I said. “Tell him your part of the presentation will take ten minutes, and tell him when in the presentation you think it should be. Then say you’re open to suggestions about whether it should be earlier or later in the presentation.”

Red or blue T-shirt? Broccoli or spinach? Offering only your preferred choices is an effective technique. It forces the person you’re negotiating with to question you, and that’s uncomfortable.

To use this technique ethically, think about how much the other person’s autonomy is your responsibility. Don’t exploit a position of power where the other person really can’t question you. But in an arms’ length negotiation, a business deal, a transaction where you have no real relationship with this person? Give it a try. Make a demand. See what happens.