Last month we talked about fully defining a problem before you try to solve it. If it seems like you and your negotiating partner are talking past each other, consider whether you both agree on what problem you are trying to solve.

(For fans of last month’s newsletter who became emotionally invested in the conflict between Person A and Person B over where to eat lunch: Albert and Bernardine had a delightful meal with their friends at Le Gros Choux, where the chef was happy to make a pre-planned custom plate that accommodated Albert’s dietary restrictions. When Albert stopped by the kitchen to thank the chef afterward, they instantly recognized each other; Albert used to stare at the back of the chef’s neck in chemistry class. Albert no longer needs to wonder what might have been.)

Ahem, back to business.

Once everyone involved in the negotiation agrees on the problem you are trying to solve, your job is to make sure you keep moving toward resolution.

Watch out for the two types of distractions that can derail your negotiation.

Rabbit holes: Arguing about details that don’t matter at this stage.

Side quests: Arguing about an issue that is relevant to the negotiating parties, but does not need to be resolved in this negotiation.

This post may or may not be inspired by working with my parents on selling their home. I will use these entirely hypothetical parents as illustrative examples.

Rabbit hole: The entirely hypothetical parents launch into a discussion about an apartment they see on a real estate website. One likes the balcony. The other is concerned about the view. However, the negotiation is about how to sell the house. By the time they are ready to move, this particular apartment will no longer be available. So the entirely hypothetical parents can argue about the view as much as they like, but it is orthogonal to the problem.

(Do you like that word, orthogonal? Engineers love to use it. According to vocabulary.com, “[w]hile this word is used to describe lines that meet at a right angle, it also describes events that are statistically independent, or do not affect one another in terms of outcome.” You can impress your fellow negotiators with your vocabulary by declaring, “I fear we have gone down a rabbit hole; while this issue is interesting, it is orthogonal to the problem, and we can therefore defer it until after the problem is solved.”)

Side quest: One entirely hypothetical parent is determined to prove that the other has been historically wrong in their determination to DIY home repairs rather than hiring help.

The issue is relevant to the negotiation, because it could affect their choices about repairing the house before selling it.

The “side quest” part is the insistence that the other person acquiesce entirely, not just to a plan about hiring a skilled contractor in this home sale, but about being wrong all those other times in the past.

Side quests require perspective to understand that you actually agree on how to solve the problem at hand, but are continuing to argue about side issues. Having this perspective is easier as an outside observer. But you can seek this perspective as a negotiator too, by pausing and questioning: what are we arguing about right now, and how does this resolve the problem?

Both rabbit holes and side quests can be detected by asking the same question: are we moving toward an outcome? If the answer is no, it’s time to redirect by reminding your negotiating partner of the problem you’re actually trying to solve.

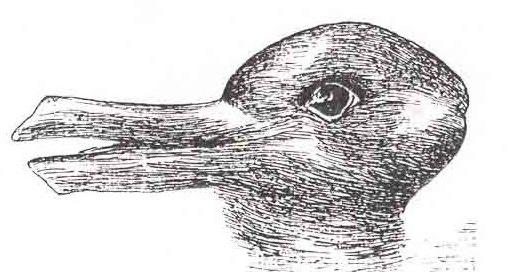

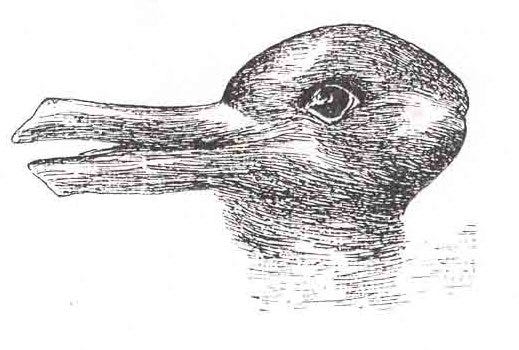

Pia, I’ve seen this image multiple times but for some reason just never saw it quite in the light that you depicted. It’s always good to see it from a different angle (other than duck or rabbit, of course)!